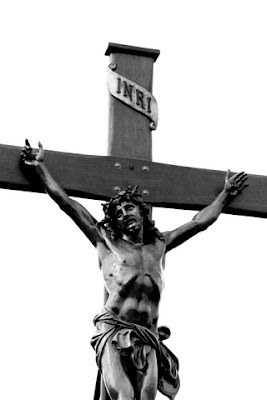

So in enters Holy Week! The most important time of celebration and reflection for the Christian world – for nominal believers it marks the promise of chocolate rabbits and the inconvenience of dashing to Church in their Sunday best, to mythicists, Easter is that all-important time to remind the world that Jesus is an amalgam of thematic responses to resurrection, death, and savior-types in other Mediterranean and Near East ancient religions. But to those of us who believe, he remains the resurrection and the life. But in what way he is the resurrection and the life remains is what I want to look at today, and it comes in the form of the doctrine of the general resurrection.

I remember listening to a debate between the late Christopher Hitchens and William Lane Craig on the question of God’s existence a few years back. During the Q&A session, in which Hitchens and Craig could ask one another questions, Hitchens became obsessed with reductio ad absurdum examples, pointing to the most extraordinary accounts in the Bible in an attempt to show their distance from the modern world. One that he picked out was the incident in Matthew 27 in which many righteous people in Jerusalem are said to rise out of their graves after Jesus dies by crucifixion.

I was actually surprised when I remember Craig’s hesitation and bewilderment at the question. I can imagine for a highly analytical Christian philosopher who is immersed in the big problems of metaphysics and reality, such a silly theological illustration would seem so childlike that it actually had the potential to create pause in him.

What could this event, which prefigures our fascination with zombie apocalypses, possibly mean? One thing I believe most scholars who attempt to salvage its meaning focus on is its link to the general resurrection, that second-century doctrine in sectarian Judaism, which asserts a salvation at the end of all things for those who would rise from the dead en masse.

Well, for my Easter exegetical reflection, I’ve been thinking about Matthew 27 alongside my conversation partner the Apostle Paul, who has a few things to say about resurrection, and what I’ve discovered is that a unified understanding of Paul and Matthew’s general resurrection doctrine does not exist.

Let’s first consider that Paul’s most important reflections on resurrection occur in 1 Corinthians, an epistle written at least twenty years before the gospel of Matthew. Here Paul uses the allegory of a seed to explain the process of death and resurrection. His famous figurative image is that of Jesus being the “first fruits of our salvation.” This has invariably come to mean among most scholars that while Jesus was not the first to raise from the dead, he is the forerunner of the general resurrection for the kind of glorification that can only occur in the bodies of those who will follow. Thus, in cross-gospel comparisons, his walking through walls to show up in rooms, his vanishings, and his concealing his appearance are all elements of the supernaturalism he’s taken up in his own post-resurrection glorified body. Therefore, resurrection is not simply resuscitation to one’s old body, but the full participation in a new life through a new body.

By 70 AD, following the Bar Kochba revolt in 64 AD, Jerusalem became a shadow of its former self. Its religious center, the Temple was in ruin, and its civil order was in disarray. For the Jew at the time, the collapse of the Temple was the collapse of his religious world. The Romans clamped down and dug in, and the Pharisaical order moved its operation entirely. Perhaps in this chaos it was easier for a small insignificant sect to suggest a story of walking zombies – perhaps because nobody took notice. But for whatever reason there are some marked contrasts between the later Matthew and the earlier Paul that don’t fit well.

Now my problem: The creed that Jesus rose from the dead in three days and at the same time was the forerunner of the general resurrection seem to go hand in hand, at least when one attempts to piece together the resurrection narrative. But Matthew creates problems for Paul and vice versa. If Matthew’s account is one of general resurrection, then it seems that the righteous dead actually rise to the general resurrection before Jesus, nullifying Paul’s claim to being the first fruits or forerunner, and the captain of our salvation. Regardless of the interpretative landscape (metaphor, symbolic, literal), this fact remains. After Jesus himself raises from the dead then Matthew reports all the other righteous ones are seen walking about in Jerusalem as well.

The problem of course is that if both Paul’s and Matthew’s account are ones of general resurrection then they don’t agree on who rises first, and by implication one most question the inveterate position that Jesus rises in three days.

Now my solution (or possible resolution):

I think most likely Matthew was trying to approximate something like the general resurrection or at least capture its essence in Jesus’ resurrection but fails to work out any an acute logic in the theological sequencing of the events. This is only a hunch because the majority of scholarship on general resurrection focuses almost exclusively on Paul as a reliable witness to the form.

There is also the issue of audience. Matthew is traditionally considered a gospel written to a Jewish audience. If this is the case, then the fact that Jesus fulfills righteousness in his death for Matthew might not have necessitated his priority over the righteous dead. The point may have been to show that Jesus should also be well-represented among those within a general resurrection that was reserved only for those righteous dead in God. I might add that this notion of righteousness in Matthew does not come through Christ (contra Paul) but appears to be locked up in the traditional community.

If, as most scholars believe, Matthew’s Jewish community was likely of post-Temple origin, then the historical background might offer some insight as well. With the destruction of the Jewish Temple in 70 AD, no doubt the center of the Jewish world had also been destroyed. One finds in the Jewish Talmud, verses equating the Temple to salvation. We know that the Temple and synagogue still played some role in the Synoptics and that by the gospel of John, the exclusion of Christians from the synagogue was complete, which makes sense since it is the latest of the four gospels. So, the promise of the general resurrection was the promise of a continued resurrection life in the community, and that all had not been lost. But given Christ’s bewildering status and rejection by most Jews, there may have been concerns and doubts, even among his followers now that the Temple was gone. It was one thing to practice Judaism in Christ and another thing to practice Christ without Judaism. Now that they no longer had the Temple to grip onto, while the Pharisaical order was busy playing damage control and enlisting the Torah as the new medium between God and humanity, perhaps the link Matthew creates through Jesus to the righteous dead is an intentional move to alleviate the concerns of his own community, given the absence of the Temple.

On the other hand, Christ without Judaism likely was not the problem in Grecian Corinth that it was in Jerusalem. Paul could speak to the Jewish mystery prophet as the first fruits of a general resurrection that was as uncontestable as it was foreign and filled with intrigue. Scholars on Near East religions know that the attractiveness of Christianity was in large part due to the collapse of the Olympian gods, which resulted in the Roman world romancing foreign religions. Of course, this did not represent all peoples. For example, Paul’s greatest challenge in 1 Corinthians 15 section on death and resurrection is not convincing his audience of Jesus’ status, but of the physical preservation of the body with the soul. And scholars are well aware that this was a Greek concern.

Now of course, one might attempt to save Matthew and argue that it took Jesus’ dying for these other ones to raise, and for that reason Jesus is the first fruits. But this is only possible if we somehow combine death and resurrection into one event, a popular tactic among Germany systematic theologians of the past century like Rudolf Bultmann, but hardly satisfying here. To this, I say with Barthian resolve: Nein! Death is not resurrection unless something occurs in between. Paul’s agricultural imagery confirms this. And at least for Matthew, the “something” that is needed occurs first in the righteous dead in Jerusalem. Jesus has not entirely replaced the traditional forbearers like Moses or Abraham, he is a part of that elite order.

But if he is of the same station as Moses or Abraham, what do we make of his godhead? Another topic, and perhaps another time.

In closing, I think what we have here are two theologies of the general resurrection in the Bible that do not fit. This shouldn’t be surprising, especially since the doctrine of general resurrection itself first crops up in those years and was most likely still being worked out.

"What doesn’t kill me, makes me stronger." - You've heard it many times. I would bet it is one of the most popular aphorisms and because of this it has been overused, reused, and abused countless times.

"What doesn’t kill me, makes me stronger." - You've heard it many times. I would bet it is one of the most popular aphorisms and because of this it has been overused, reused, and abused countless times.